King Range National Conservation Area Aquatic Amphibian Biodiversity Assessment

Aquatic Amphibian Biodiversity Assessment on the California Lost Coast

Background

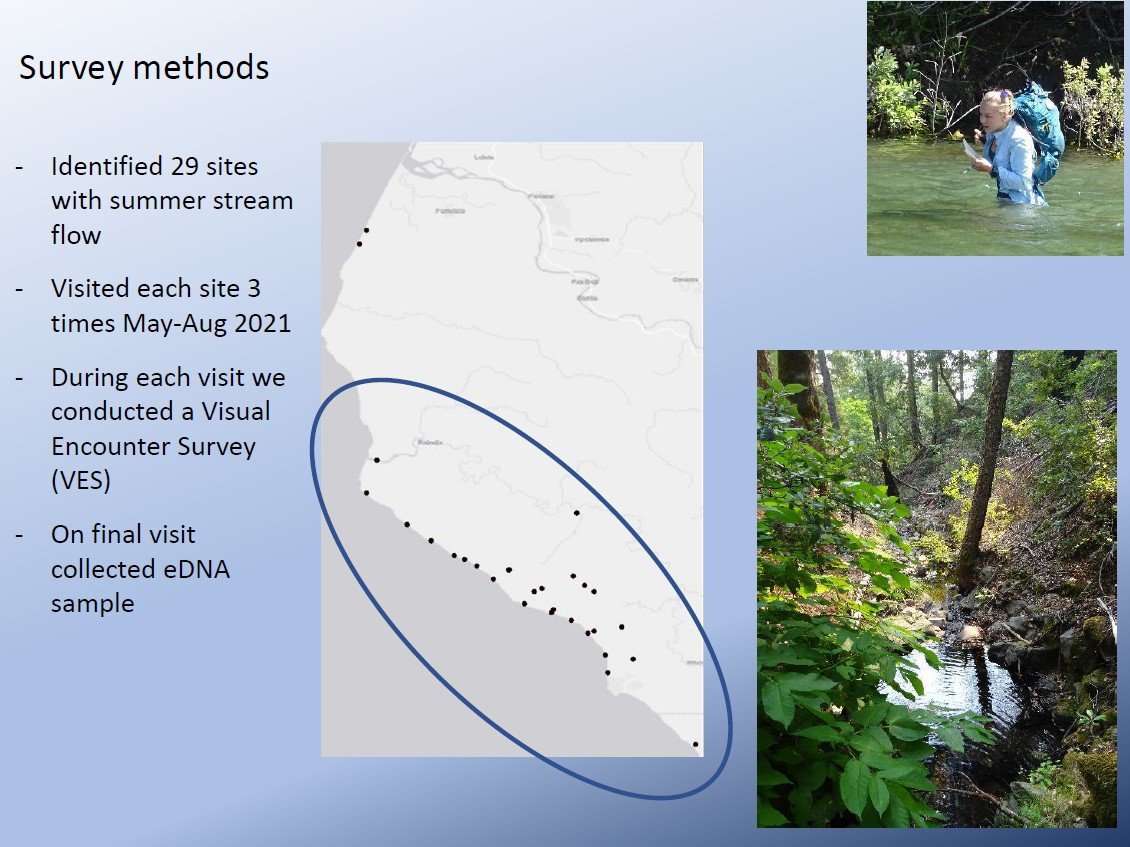

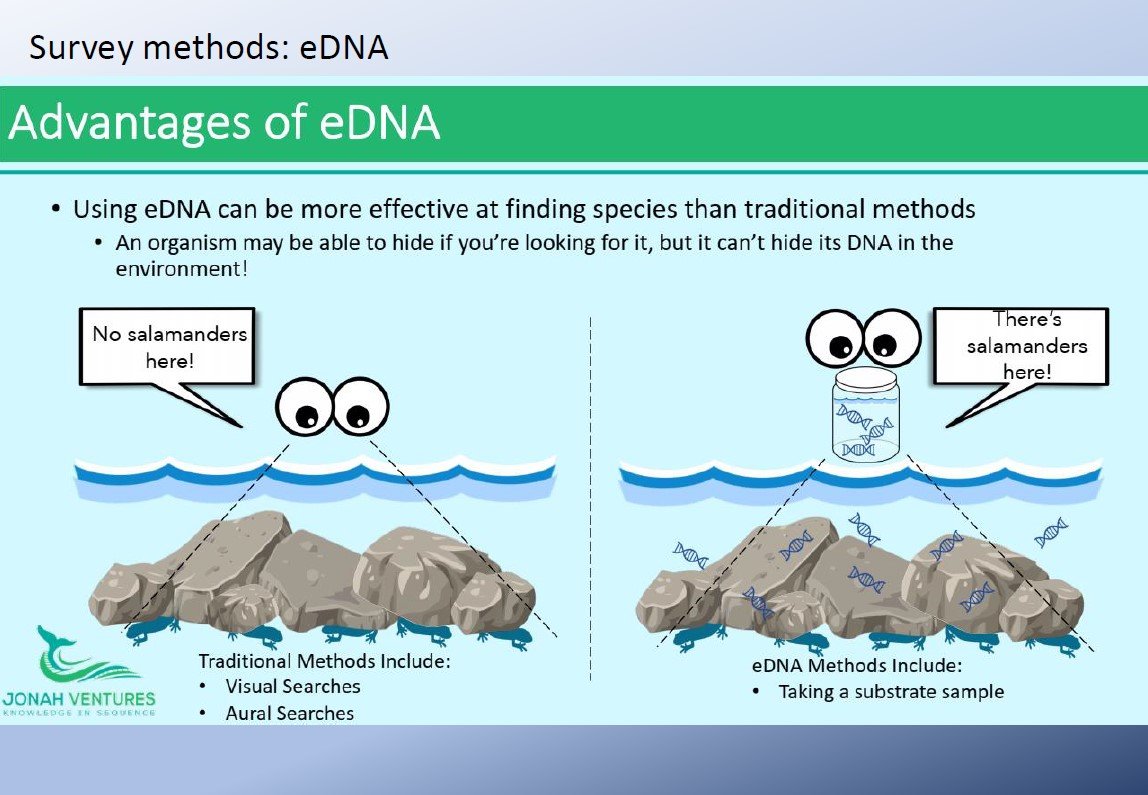

Amphibians are currently predicted to lose as many as one third of their populations within the next half century. Like many other endangered species, the key factors contributing to population decline includes climate change, habitat loss and increase in human interference. As pressure from anthropogenic stressors becomes increasingly common, it becomes more difficult to collect baseline information from healthy amphibian communities. In an effort to identify intact, healthy amphibian communities, the Institute for Wildlife Studies, conducted extensive surveys within and adjacent to the remote King Range National Conservation Area of Northern California using a combination of environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling and visual encounter survey methods to identify stream dwelling amphibians.

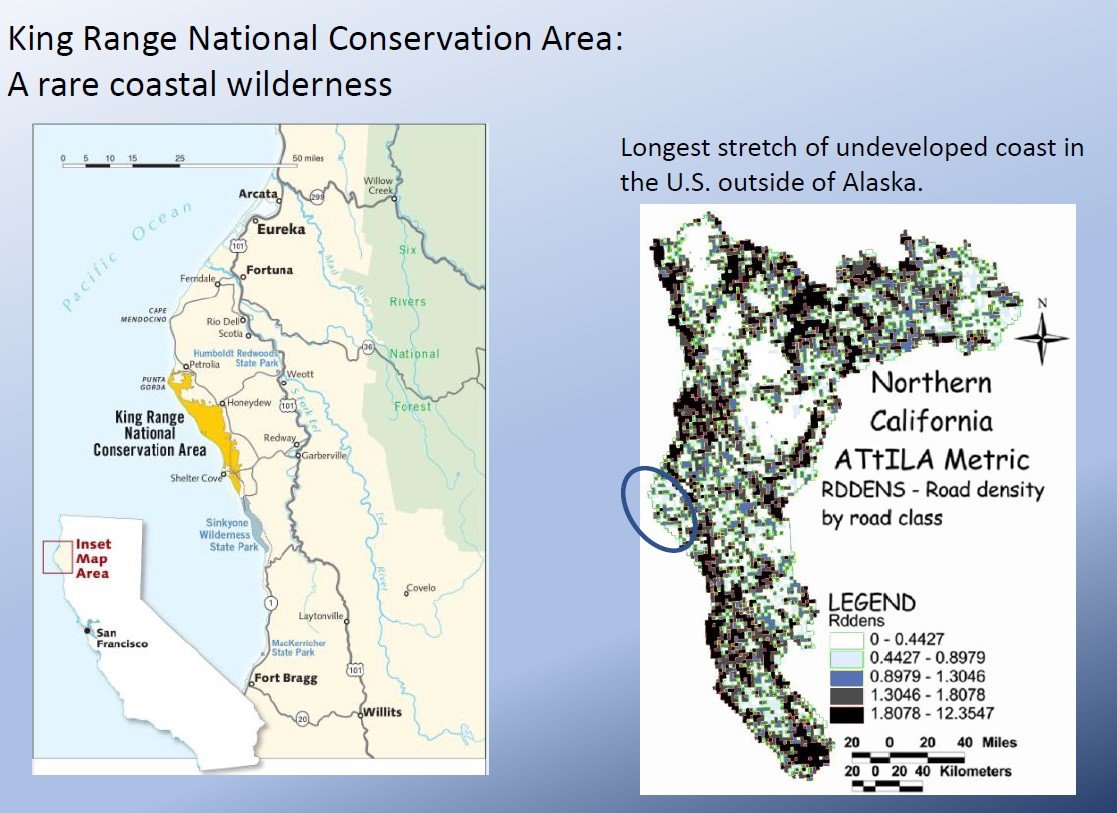

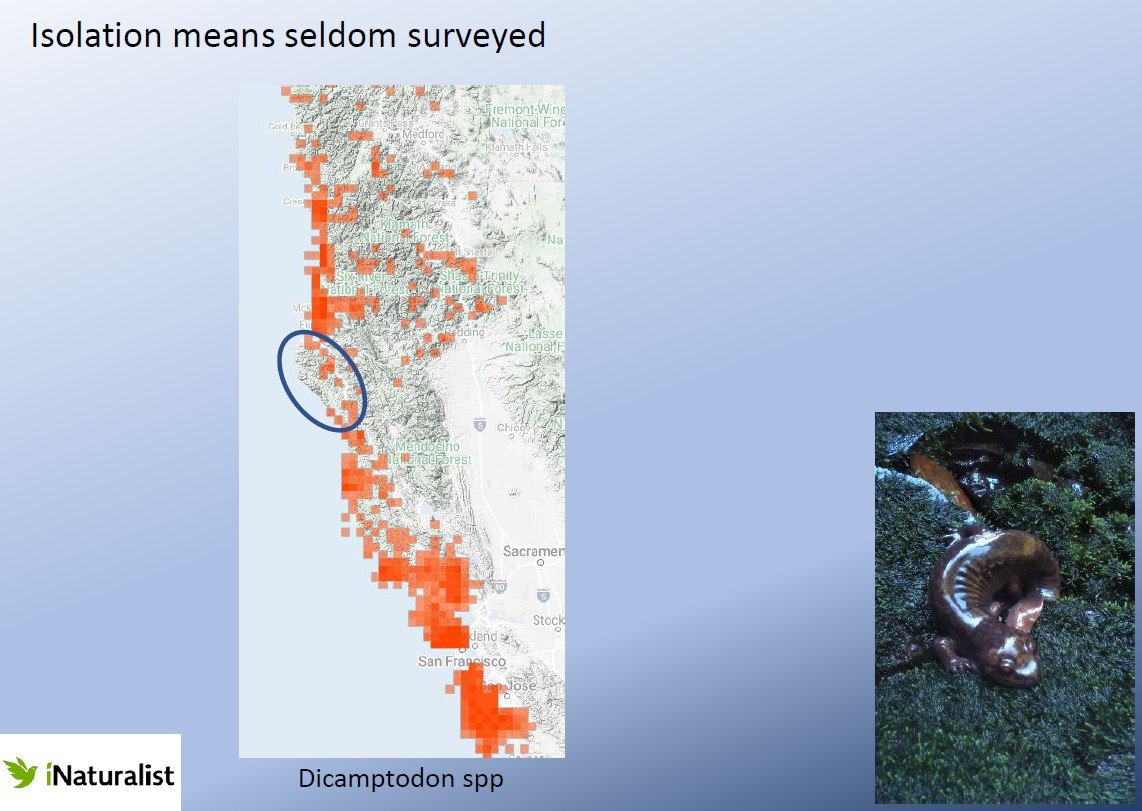

Study Area

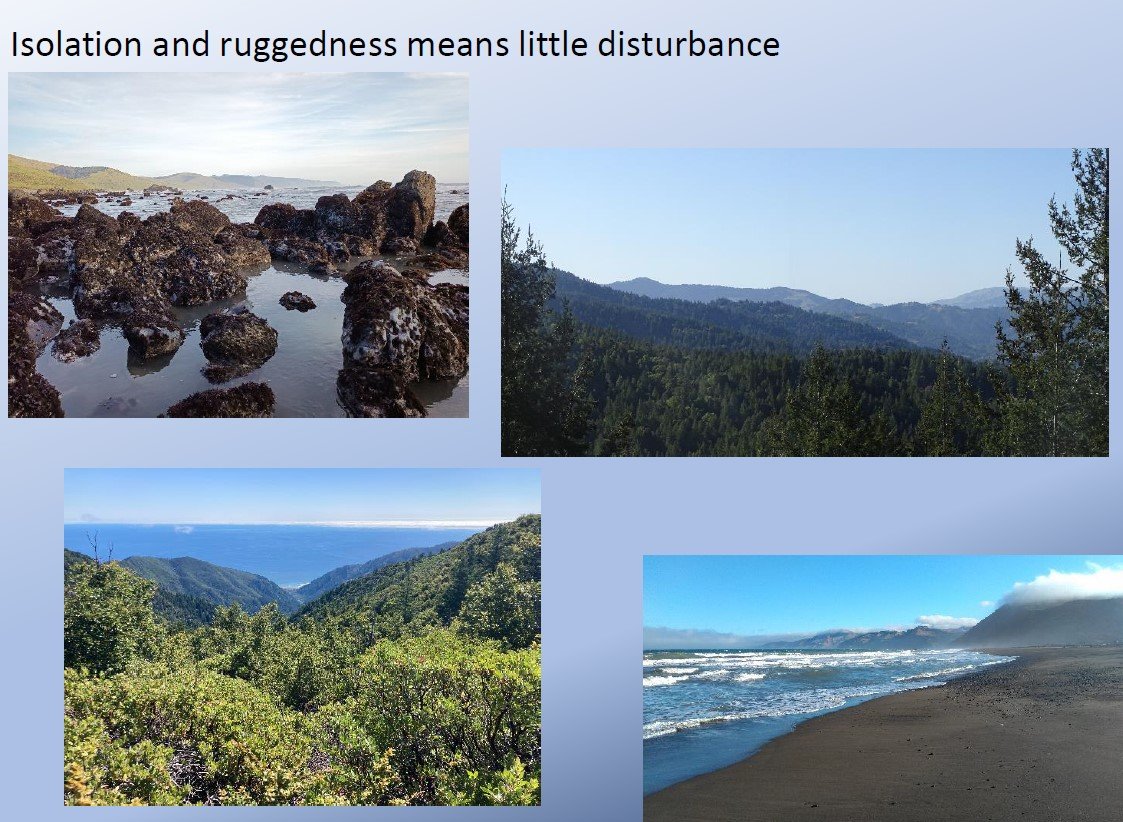

The King Range National Conservation Area is located within the aptly named “Lost Coast” region. Located over 250 km north of the nearest metropolitan area (San Francisco, CA) and over 50 km from the nearest town with a population larger than 15,000 (Eureka, CA), it remains isolated from urban and suburban development pressures. Few roads access the Mattole River along the eastern edge of the King Range National Conservation Area and none cross the ocean-draining watersheds within it. The Lost Coast region consists of some of the most rugged terrain in California. The majority of the streams in this study consist of extremely steep rocky slopes descending from mountain peaks to the Pacific Ocean or Mattole River, with the summit of the highest peak, the 1,246 meter King Peak, less than 5 km from the ocean. Likewise, the weather and tidal fluctuations are extreme. The only access to much of the area is to travel along the Lost Coast Trail, and large stretches of this trail are only accessible at low tide, a few hours a day. Weather changes rapidly. Winter storms frequently make the area inaccessible for weeks at a time, and summer days often start with dense fog in the mornings and high temperatures in the afternoon, with unexpected rain showers. The inaccessibility of the terrain and unpredictability of the weather have ensured the ecosystem has remained largely unaltered. Peaks are primarily covered with native douglas fir, with coastal grassland plains closer to the ocean.

Results

We found a total of twelve species associated with streams in the study area. These species included all stream-dwelling amphibians native to the Lost Coast, and western pond turtle, the only freshwater turtle native to California.

One species notably absent from the study area was the American bullfrog. This frog, native to the southeastern United States, was introduced to California around the turn of the 20th century to use their legs as a food source. Now found throughout the Pacific Northwest, bullfrogs are voracious predators, often consuming or outcompeting native frogs and salamanders. Together, the absence of bullfrogs from the Lost Coast and presence of all native stream-dwelling amphibians indicate that the King Range National Conservation Area and surrounding areas contain a vibrant and intact stream-dwelling amphibian community.

Amphibian Diversity Assessment Presentation:

Species Identified:

An eDNA mystery

Our study also revealed an underappreciated limitation of eDNA surveys: data gaps in the eDNA library. Some species such as bullfrogs, Pacific chorus frogs, and rough-skinned newts, are well represented, such that any DNA strands from these species collected during our survey would have matched a published sequence. Other species were less well characterized, but still had their entire mitochondrial DNA sequence represented (black salamanders and southern torrent salamanders). If their DNA was present in our samples, it was likely they would have been identified if an amplification primer targeted a mitochondrial sequence. On the other hand, most species were significantly underrepresented, with orders of magnitude fewer sequences available for comparison. Because of these data gaps in the DNA library, we were unable to determine if eDNA fragments matching giant salamanders from the genus Dicamptodon were from the coastal giant salamander (D. tenebrosus), California giant salamander (D. ensata), or both.